It was a group of fishermen who noticed something strange was brewing at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea.

Before 1831, the waters off the south-western coast of Sicily had been best known for their coral, which is still prized by jewellers today. In July of that year, however, Sicilian fishermen had started to notice shoals of dead fish rising to the ocean surface – as if they had already been boiled by the ocean. The fish were edible, but they stank of sulphur. (The fumes were apparently so strong that some of the fishermen lost consciousness.)

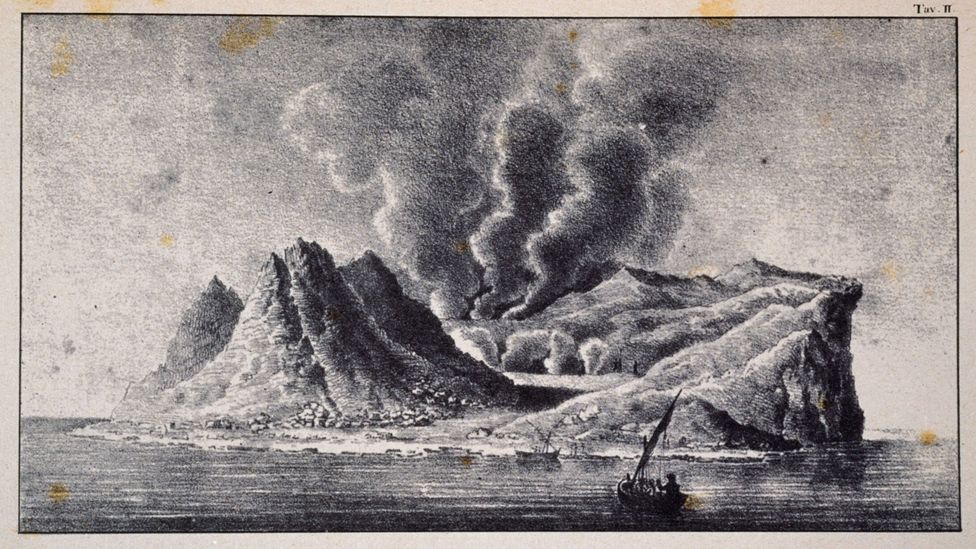

The cause of the fish deaths became clear a few days later on the night of 10 July, when sailors noted that the mouth of a volcano had emerged above the waves, sputtering smoke, ash and lava. It grew and grew, and by August a whole island had formed.

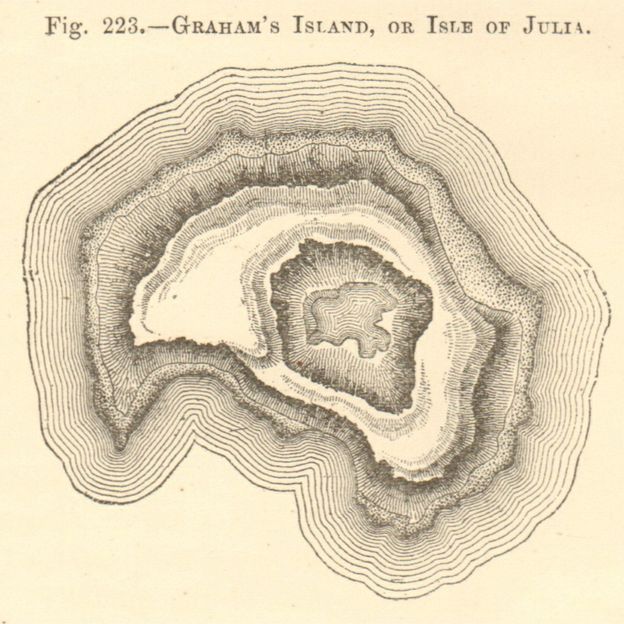

The island was little more than a rock – around half a mile (800m) in diameter and 200ft (60m) above the sea – but it was full of possibilities; many people even believed that they were observing the birth of a whole new continent.

The island arose in a strategic position, and was promptly claimed by Italy, Britain and France (Credit: Alamy)

Located at the heart of European shipping routes, the island soon led to an international dispute, as France and the UK competed with the Sicilians for the island's ownership. The argument was all for nothing, however. Within five months, the island had sunk back below the ocean surface, leading some to name it "L'isola che non c'è" (the island that isn't there) or "L'isola che se ne andò" (the island that went away).

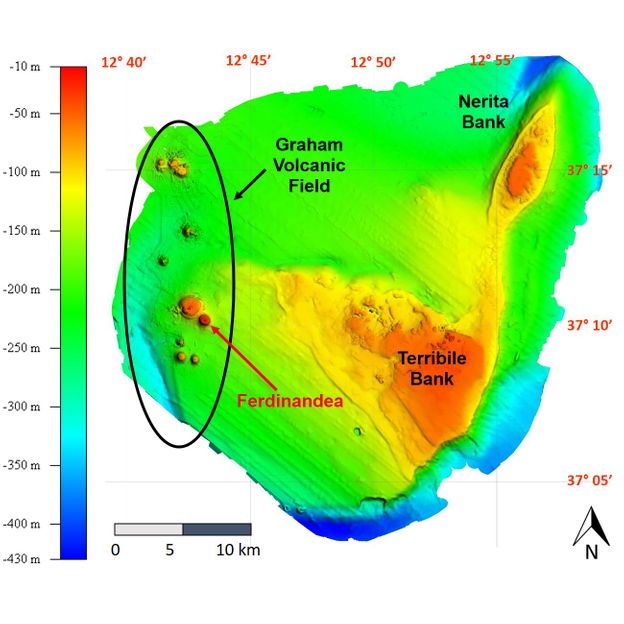

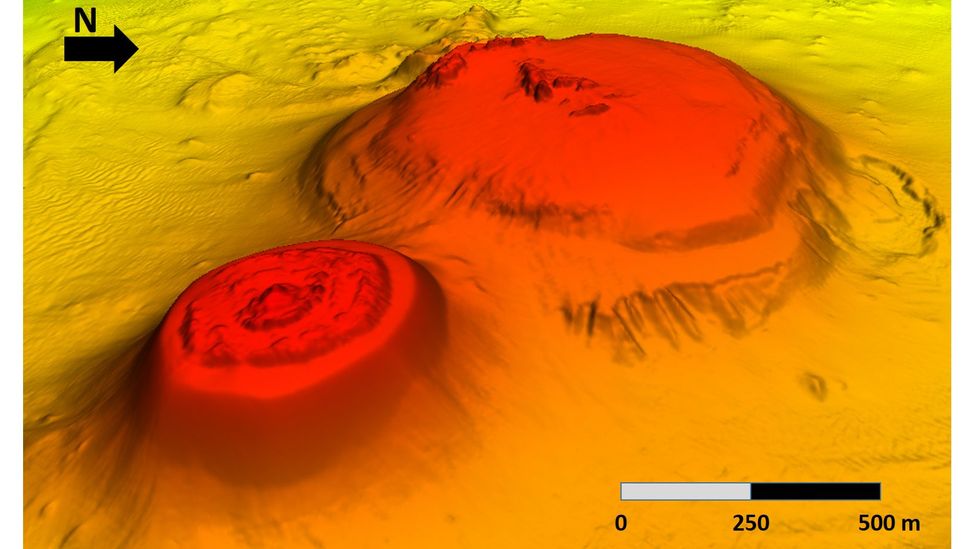

This month marks the 190th anniversary of the island's emergence. Volcanologists have been able to map the sea floor around the Sicilian strait in extraordinary detail, with astonishing images of this short-lived Atlantis. Their work can help us to understand why it emerged and disappeared – and whether a new island may ever rise in its place.

The stuff of legends

Sicily's history is intertwined with the region's seismic activity. Historians have discovered Greek writing from more than 2,700 years ago that refers to eruptions on Mount Etna, which remains one of the world's most active volcanoes. Two of Etna's worst eruptions, in the 12th and 17th Centuries, are thought to have resulted in tens of thousands of deaths.

Sicily has also been shaken by severe earthquakes, including the famous Val di Noto quake of 1693 that killed 60,000 and destroyed the city of Catania, and the 1908 earthquake in Messina that took 82,000 lives.

King Ferdinand II ruled Sicily as well as part of mainland Italy, including Naples, which together were known as the Two Sicilies (Credit: Getty Images)

Without a modern understanding of seismology, the Sicilian population had created a rich mythology to explain these tragic events. "Legends help people to live with this ancestral fear, and justify the existence of the phenomena," explains the writer Marinella Fiume, whose book Sicilia Esoterica examines Sicily's rich folklore and traditions.

According to one legend, there was once a young fisherman, Cola, who was famous for his ability to stay under water for long periods of time, earning him the nickname Colapesce – Cola the fish. Hearing of his talents, the king challenged Colapesce to recover numerous objects from the sea floor. On one of these submarine missions, the fisherman discovered that one of the columns, supposedly supporting the island, had been damaged by Mount Etna's fire. To save Sicily from sinking beneath the waves, Colapesce took it upon himself to replace the broken column. "In certain versions of the legend, Colapesce rises to the surface every hundred years to see the land again – and it is these movements that provoke earthquakes and tremors," says Fiume.

Today, we know that Sicily and its waters sit on the boundary between the Eurasian and African tectonic plates. The movement of the plates can cause tension to build in the Earth's crust, which results in earthquakes. The ongoing movement forces the African plate underneath Eurasia, meanwhile, pushing it into the mantle. This leads to build-up of melting rock, which can break through weak points on the Earth's surface, leading to volcanic eruptions.

Mount Etna and Mount Vesuvius are the most visible examples of this, but eruptions can also occur underwater, as magma rises through weaknesses in the crust below the sea floor. A series of submarine volcanic cones can be found around 25 to 40 miles (40 to 64km) off the south-west coast of Sicily. They are "monogenetic", explains Danilo Cavallaro at the Etna Observatory in Catania, which is part of Italy's National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology. This means that each cone results from a single eruption.

With the advent of modern volcanology, the seafloor of the area has been mapped in extraordinary detail (Credit: Danilo Cavallaro)

"The magma rises up through a conduit – and after the eruption, it cools and crystalises, forming very hard rock," he says. During any further eruptions, the magma will flow around this and break through the surrounding softer rock, instead, producing a brand-new cone.

Cholera and chaos

The eruption of 1831 occurred at a tumultuous time in Sicily's history.

Italy, as a single unified country, did not yet exist, and the island of Sicily was part of a state that covered the south of the peninsula. This included Naples, which, historically, was also known as Sicily, leading the state to be called the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and it was ruled by King Ferdinand II, who had come to the throne in November 1830.

The new king wasn't accepted by everyone, however, and by 1831, some members of the public were already plotting against his sovereignty, says Filippo D'Arpa, a journalist and author of the book L'isola che se ne andò(The Island that Went Away). The population also faced the threat of a cholera epidemic, for which there were no proven cures and no end in sight – a situation that feels all too familiar to readers today.

Amid this turmoil, the appearance of the new island off the south-western coast of Sicily seemed like something of a distraction to the average citizen. "The events were perceived as a problem for the noblemen," says D'Arpa.

The location of the new island did, however, mean that it was of great interest to King Ferdinand II – and to the governments of other European countries. "Let us remember that the Suez Canal had not yet been created," says Nino Blando, a historian at the University of Palermo. "And the island's position was particularly favourable to control the commercial passages along the route to the Middle East."

While dramatic, the island arising from the sea was considered something of a distraction amid a tumultuous period in Sicily (Credit: Getty Images)

Even more importantly, the waters around the island were infested with "privateers" – state-sanctioned ships who were allowed to loot merchant ships from enemy countries. England, France and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies all had their own privateers, who were mostly engaged in a "war" with ships from the Ottoman empire. The newly emerged strip of land, off the coast of Sicily, could have therefore helped its owners to gain control of the waters.

Little wonder that each country tried to claim the island for itself.

Given the island’s location, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies might appear to have had the most convincing case. The island lay between the coastal town of Sciacca, and Pantelleria, another, much more ancient, volcanic island that was already part of the kingdom's territories. They called it Ferdinandea, after King Ferdinando II.

Unfortunately for the Sicilians, English sailors claimed to have been the first people to set foot on the new-formed island. They claimed it was terra nullius – free for anyone to occupy – and planted their flag. They named the island Graham, to honour the First Lord of the Admiralty, Sir James Graham. (Graham had never actually visited the island.)

France did not want to miss out on the opportunity either. The country sent surveyors to map out the terrain, and planted their flag on the highest point of the island. They called it Julia – after the month of the island's birth.

Today, the mass of the island can still be traced clearly in the seafloor, but it remains many metres below sea level (Credit: Danilo Cavallaro)

The dispute continued for five months, during which time, the once 200-ft-high (61m) island had already started to sink. "At the end of September, it was some 60ft [18m] high. One month later, it was only a few feet high. And finally, between December 1831 and January 1832 – it completely disappeared," says Cavallaro. The problem, he says, is that the island's base was mostly formed from scoria rocks – also known as "cinder". "They are very fragile, and can be very easily eroded by sea waves," says Cavallaro.

Quite astonishingly, France's surveys had warned of this possibility, yet the country had continued to claim ownership of the quickly disappearing piece of rock.

Finding Neverland

The promise of another strategic foothold in the Mediterranean may have ended in disappointment for all three parties, but the short-lived island proved to be an inspiration for many writers, including Jules Verne. "He got to know the island's story because it was well-known in France among the societé geologique," says Salvatore Ferlita, a professor of Italian literature at Kore University in Enna. The writer mentioned the island in the novel In Search of Castaways and it became the treasure island in his later novel Captain Antifer. It is even possible that JM Barrie's Neverland – the home of his most famous creation, Peter Pan – had been inspired by "the island that wasn't there", Ferlita says.

Between myth and legend, and despite its disappearance, the island has never left the popular imagination, and over the subsequent two centuries, apparent signs of volcanic activity have raised hopes that the island – or one very like it – may one day return to the Strait of Sicily.

One of the most notable events occurred in 1968, when an earthquake in the region was followed by the apparent boiling of the seawater around the former location of the island. This led some to believe that the events of 1831 were set to repeat themselves. The Sicilians were not going to risk losing ownership of the island, and Blando says that they placed a stone plaque on the relics of the island to assert their rights. It read: "This strip of land, once Isola Ferdinandea, did, and always will, belong to the Sicilian people."

It is thought that Ferdinandea may have been an inspiration for Neverland, in JM Barrie's famous tales of Peter Pan (Credit: Getty Images)

The island never materialised, however. The bubbles in the seawater, Cavallaro says, were simply the result of gas, trapped between layers of rock, that had risen to the ocean surface. It created the illusion that an eruption was brewing, but there was never really the possibility that the island would return. When there is another eruption in this area, it will occur at a different location, he says – since the rock from the previous explosion will have stoppered the conduit for magma.

Cavallaro's team recently mapped the volcanic field on the seabed of the Strait of Sicily. Their images include the remains of the island, which sit next to a much older volcanic cone from around 20,000 years ago. Today, Isola Ferdinandea lies around 30ft (9m) below sea level and 450ft (137m) above the seabed. "It's an almost perfect truncated cone with very steep slopes," Cavallaro says. There is a peak in the middle, he says, that marks the upper portion of the conduit through which the magma first erupted. Today, it is fully colonised by coral, he says – and home to many species of fish.

The island may never again rise above the waves – but its story helps remind us of the enormous geological forces shaping our landscape, which give and take in equal measure.

--

Alessia Franco is an author and a journalist focusing on history, culture, society, storytelling and its effects on people. She is @amasognacredi on Twitter

David Robson is the author of The Intelligence Trap: Why Smart People Make Dumb Mistakes, which explores the best ways to improve our thinking, decision making and learning. He is @d_a_robson on Twitter.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

"Short" - Google News

July 09, 2021 at 06:07AM

https://ift.tt/3jZtLBS

The Mediterranean's short-lived 'Atlantis' - BBC News

"Short" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2QJPxcA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Mediterranean's short-lived 'Atlantis' - BBC News"

Post a Comment