This story is part of Future Tense Fiction, a monthly series of short stories from Future Tense and Arizona State University’s Center for Science and the Imagination about how technology and science will change our lives. This story and essay are the second in a series presented by Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, as part of its work on Learning Futures and Principled Innovation. The series explores how learning experiences of all kinds will be shaped by technology and other forces in the future, and the moral, ethical, and social challenges this will entail. On Thursday, April 1, at 5 p.m. Eastern, author Shiv Ramdas and Katina Michael, professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society and School of Computing, Informatics and Decision Systems Engineering at Arizona State University, will discuss this story in an hourlong online discussion moderated by Punya Mishra, professor and associate dean of scholarship and innovation at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. RSVP here.

From the moment the text message arrived with an aggressive ping, Ahmed knew something was amiss. Oh, it read innocuously enough, just the one line from Niyati asking if they could have a chat, but he knew better. It was still two weeks before his meeting with the tenure committee, which made it unexpected. Plus, it was Those Words. Whenever someone said that they wanted to have a chat, what they actually meant was that they had something to say to you that they knew you wouldn’t like one bit. At a theoretical level, Ahmed knew that there must have been occasions in human or even academic history when the phrase have a chat had resulted in happy times and good vibes, but he wasn’t aware of a single one.

He checked to make sure his phone camera and mic were working properly and clicked on the link Niyati had sent him and a moment later when he arrived in the virtual meeting room, he found her already there, waiting for him.

“Hi, Niyati!” he said, with a breeziness he wasn’t feeling in the slightest.

“Hi, Ahmed,” smiled Niyati. “Thanks for doing this at such short notice.”

Maybe it was the smile, or just the familiarity of the usual start-of-meeting inanities, but Ahmed was already feeling much better. This was probably just a friendly heads-up about some part of the process. Niyati had told him privately more than once since the end of last semester that tenure was practically a done deal; everyone, including the Old Man, was thrilled with his classes; the student feedback had been glowing and he had nothing to worry about this time. Remembering all this, he felt the stress melt away. For the first time since he’d seen that text message, he was feeling cheerful again.

“Ahmed, we’ve had an … um … change in plans.”

So much for being cheerful.

“This is about my tenure, isn’t it?”

She started to shake her head, and managed to turn it into a nod midway, which somehow made it worse than if she’d just agreed.

“To recap what we’d discussed last year, a few more publications would really have helped us market the entire creative writing program, as the Board has pointed out, but as you know, you haven’t really had any. A novel or two would have been really helpful.”

“Novel or two? Yes, why not, what with all the time you’ve left me to—”

“Just hear me out, Ahmed. You’ve been with us for seven years, and in the last couple, you’ve been exceedingly productive on the teaching front, and we want you to know that we value that.”

“I should hope so—you keep asking me to teach extra classes! And added students to my existing classes for each of the past three years.”

“I think I speak for everyone when I say we deeply appreciate your efforts to help out during this period of budgetary readjustment. But this is about more than just your tenure prospects. What I’m about to discuss with you involves not just your future and mine, but that of the department, the university—of education itself. As you know already, the university has been focusing on innovation and how we can best provide the educational experience students need in the modern world. We want to perfect a hybrid class that simultaneously caters to both the real and virtual spaces. To that end, the university is investing significantly in our digital architecture. It’s going to be a truly unique experience. And it’ll do wonders for our student intake, especially when it comes to international admissions. You know how hard it is to get Westerners to come study in India, I’m sure. This will be a truly pioneering educational innovation, where you can learn the same way at the same time from the same teachers as a student on the other side of the world. The next step in achieving a state of true value addition at every step of the learning process.”

“You memorized that line, didn’t you?”

“Yes. And the rest of it too. Right off the new brochure.”

There was a short, heavy pause. Niyati broke it first. “Look, none of this is my idea, all right?”

“That’s what I thought.”

“It’s not me, it’s the Old Man. Administration’s in his ear good and proper now, and by that I mean Uma from Administration. Full of great ideas, Uma, and somehow all those ideas involve someone doing something ridiculous that helps Uma’s annual review. All those extra students and classes you were complaining about? Uma’s brainchild. The field trip reductions? Uma. It’s all about the numbers with that one.”

“Can’t you just—”

“No. Believe me, I’ve tried. Now let me finish.”

“Wait, there’s more? How many horrors do you have up your sleeve?”

“Uma’s tireless, I told you. Now like I mentioned, the feedback from your students has been excellent and you’ve always shown exceptional skills as a teacher. This is why we’d like you to be an integral part of the rollout of the new academic design.”

“Not enough to be tenured, though?”

“As a matter of fact, there is an opening for one tenured position, the only offer we’ll be tendering for the foreseeable future, I’m afraid. That’s what I want to discuss with you, Ahmed. What I’m about to propose will give you a legitimate shot at securing that tenure.” She paused. “I’ll be honest, it’s pretty much your only shot.”

“So another year to get my tenure?”

She pursed her lips. “Not exactly. We have a rollout plan for this process already in place. It’ll be for one semester only.”

One semester wasn’t nearly as bad as he’d anticipated. Ahmed smiled.

“At the end of which we’ll be looking to downsize the department.”

Ahmed’s smile vanished.

“The plan is to retain just the one tenured professor by the end of next semester. I just want you to know I have every confidence in you and I have no doubt you’ll be the teacher the students would rather have at the end.”

“At the—you’re going to tell me something else I’m not going to like, aren’t you?”

“What part of this have you liked?”

She had a point. “All right, I’m listening.”

“Well, Uma suggested at the last budget meeting that the best way to streamline the department—”

“You mean sack everyone.”

“Technically, it’s what Uma means, but yes. Long story short, you’ll be splitting your classes with the new teacher.”

“What new teacher?”

“Ali.”

“Who the hell is Ali?”

“Well, that’s just what we call it.”

Ahmed sat up very straight. “It?!!”

“Yes, it. Ali’s a robot.”

Ahmed blinked. “I think there was an issue with the connection, it sounded like you said robot.”

“I did say robot. Well, A.I. Something like that, I’m not exactly sure. Look, it’s a machine, all right? I think the full name is Augmented Learning Interface. You can see why Ali took off.”

Ahmed took a deep breath and spoke slowly, emphasizing each word.

“You want a robot to teach creative writing?”

“Uma produced this whole body of research proving that modern A.I.s are extremely deft with prose and craft construction, though they sometimes struggle with plot development. They’ve even been known to come up with some really creative, out-of-the-box solutions to problems. You can see how that’s an asset, right? The escalation of stakes is the only—”

“Niyati, it’s a goddamn robot. Now let me get this straight, you want me to take part in a teaching contest against this … thing? For tenure? And a job? As a professor of creative writing?”

“Basically.”

“And this is Uma’s idea?”

“Well, it was the compromise.”

“Oh, this was the compromise. Great. What was the original, did Uma want teachers to fight to the death for tenure in a sealed classroom? I’m sure the pay-per-view would be great revenue.”

“Don’t be ridiculous. Nobody’s going to pay to watch teachers fight when they can just see it for free on social media. Anyway, the way we envisage this playing out is having you both teach the same class of students. We’ll be splitting each of the courses up, dividing the load between you both.”

“So each of us is teaching half of each course for the whole semester?”

“Exactly.”

“This is beyond asinine and you know it.”

Niyati sighed. “I’m not stabbing you in the back, I’m trying to save your butt, Ahmed. Help me help you, huh? OK? I trust you to prevail. We’ll be assessing the class at the midpoint and end of the semester, and then we’ll be making a decision on whom to tenure. Now what else? Ah, yes, the assessment. Now, the assessment metrics will be simple, a weighted combination of student feedback, the university’s own assessment—you’ll have observers in a few classes by the way—and finally, the student scores.”

“Scores? How the hell does that make sense, I’m grading them.”

“We’ve worked out a system, don’t worry. Anyway, that’s everything I needed to cover. You’ll be getting a formal communication about it, but I told the Old Man I wanted to make sure I could give everyone the heads-up. Now, any questions before I get to the hard conversations?”

“Besides what I’m even doing with my life?”

“That’s one’s for your therapist.”

“OK, what hard conversations?”

“The ones I’m going to have with the others in the department right after I get off this call.”

She didn’t elaborate, but she didn’t need to.

“You’re really going to get rid of everyone else? You’re going to head a department of three?”

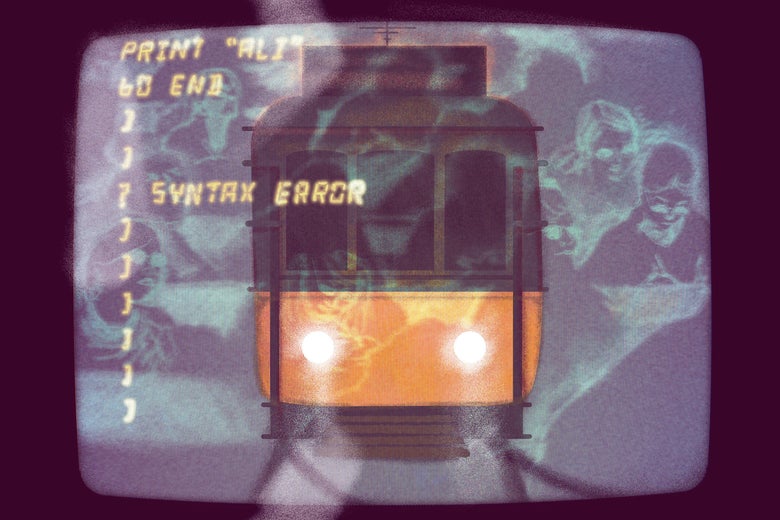

“It’s either that or the whole department. I have no choice, it’s like the trolley problem all over again.”

“Oh, is that what it’s like?”

“My advice would be that you should probably connect with Ali at some point before the semester, too. It might help, ah, orient you a bit.”

He didn’t reply, there didn’t seem anything left to say.

“Oh, and Ahmed?”

“Yes?”

“I’ll be rooting for you. You got this.”

He managed a thanks, and logged off, although it was a long time before he stopped staring at the now-blank screen. He had survived the purge, for now, which was something.

Ahmed sighed, a long mournful sound.

Then he logged back into his email to welcome the machine that had been brought in to take his job.

The last few weeks had gone by in a blur, just like everything else ever since he’d got off the call with Ali, which in itself had been just as bizarre as he’d anticipated.

Ahmed wasn’t sure what he thought he’d find, but a disembodied colleague, visible only as a blank window where a face usually was that said “Augmented Learning Interface” hadn’t been it. But what really threw him was the voice, which hadn’t been the sort of tinny, robotic timbre that movies had led him to expect a robot should possess. Instead, Ali had spoken to him in warm, familiar tones with a strong Western Uttar Pradesh accent that reminded him of home. It turned out Ali had access to a dizzyingly vast array of voices and accents, supposedly to help it engage better with a diverse student body. Yes, the call had been illuminating, to say the least.

Ahmed glanced at his watch. Still time to read a few more emails before the next class. These days he found himself looking forward to this part of his day, mostly because it reminded him of the good old days when teachers were just underpaid and undervalued instead of also having to also prove they could out-teach robots. Most of the emails were the usual fare. Cathy wanted a deadline extension, Zhang wanted to clarify something said in class, Marcus wanted to retract something he’d said, Mayil wanted to be able to do his collaborative projects this semester with the other student from Tamil Nadu, and Lamar, one of the U.S.-based students, had written in explaining that he hadn’t finished the last assignment because he’d requested and been granted extra hours at his high school in order to help work off his school lunch debt and could he please have an extension? Ahmed responded with practiced ease, agreeing to all of them except Mayil, to whom he sent his usual gentle missive about how working with students from different parts of the world was a huge opportunity. The final email in his inbox was from Debanjana, who’d asked if she could speak to him before class. Ahmed sent her a link to a meeting room, wondering if something was wrong. At least she hadn’t said she wanted to “have a chat.”

The class itself had gone as well as could be expected, just as most of them had so far, even if it had just been three weeks since the semester had begun. Since then, his only contact with Ali had been through the cordial, businesslike notes they’d exchanged about the sequencing of assignments as students rotated through their respective classes. The real wrinkle had been getting used to the observers who were there in every class, silently taking notes. But he wasn’t going to allow that to deter him. No way would he let a machine turn out to be a better creative writing teacher than he was. “Hi, Debanjana,” he said, once the computer’s beep advised him she was on. “Nice to see you.” And he meant it, this particular student had already made quite the impression on him.

That was when he noticed the tear smudges on her face, the slight quiver of her lip, and the set of her jaw.

“Is everything all right?” he asked, knowing that it wasn’t.

“I’m having an issue, professor.”

“Tell me?”

“Ali, I mean Prof—I mean … ” Her voice trailed off.

“Yes, yes, go on.” He didn’t know whether a machine could even be a professor either. “You can just say Ali, it’s fine.”

She smiled wanly. “Thank you, professor.

“In Prof—in the other class last week my answers were either ignored or misunderstood. It’s happened a few times. I spoke about it, and I was told that it was not yet calibrated to understand me.”

“Excuse me, say that again?”

“I was told my tendency to use idiomatic phrases was causing Ali difficulty with context and it wasn’t my fault but I’d have to be patient.”

“This sounds unfair, to say the least.”

She nodded. “I’ve stopped speaking in those classes, but when I mentioned that, I was told I shouldn’t do that as getting things wrong was the best way to calibrate and it would also help others in the future.”

“Who said this? Ali?”

She shook her head. “I wrote to the University Administration and I got a reply from someone called Uma.”

Ahmed could feel the slow, hot flush of anger spreading through him. He took a deep breath. “I see.”

“So what do I do, professor? Should I keep speaking and being misunderstood so that one day others will not be?”

“No, of course not. With your permission, I think I want to address this.”

She shot him a grateful look. “Thank you.”

“Of course. Thank you for telling me about this.”

A few moments after his conversation, he reached again for his phone and typed:

“Hi Niyati, can we have a chat?”

A week later, he was still thinking about his conversation with Niyati. It hadn’t exactly gone the way he’d hoped.

“Hi Ahmed, sorry it took me so long,” she’d said, when she finally arrived in the meeting room, almost half an hour late. “I’ve just been drowning in preparing these presentations for prospective investors and—anyway, it doesn’t matter, you wanted to talk? What’s wrong?”

So he told her, noting how she’d sat there, stone-faced.

“I’m not going to name the student, obviously, but we have a serious issue we need to address,” he’d finished.

“I spoke to her.”

“When?”

“Last week. I escalated the matter to the Old Man and the situation is being monitored. But remember, Ali’s intent was obviously not to disregard the student. Uma pointed out that if there’s an issue, it’s obviously at the programming end. This is the first time something like this has been tried, there’s bound to be some teething troubles.”

“How do intentions matter? It’s the impact on the students that we need to prioritize. If this were a human teacher would they be getting leeway for intent?”

She didn’t answer. Sensing an opening, he went on.

“How are we supposed to provide this cutting-edge education you were talking about when we can’t even make sure students are understood properly? This is simply unacceptable!”

Niyati ran a hand through her hair.

“Look, Ahmed, I’ve tried. Believe me, I’ve tried. But the University has invested too much and Uma has way too much riding on this initiative.”

“Ali is simply not qualified. You know why machines have issues with plot development? Because they struggle with context. And consequences. Intelligent decision-making is one of the hardest programming design issues out there. And might I add, this is exactly what I was worried about. A machine can’t teach writing, hell, I don’t know if it can teach anything but it sure can’t teach writing if it struggles with context. Not to mention stakes and conflict.”

“Ahmed, my hands are tied here. I’m just telling you what Uma said.”

“Oh, hang Uma!”

“I wish,” said Niyati, with feeling. “Look, I’m tired of all this too. Once we’re done here I have to go back to trying to meet revenue targets.”

“What revenue targets?”

“The ones I have to meet now, because guess what, we’re also in the process of moving to a hybridized admin-academic model.”

Ahmed was starting to feel lost. It was as though he’d entered some strange parallel dimension, where the words all sound the same but have completely different meanings.

“When did we go from being a university to a live-action dystopian role-play?”

“When Uma became the only administrator the Old Man and the Board will listen to anymore. It’s all about revenue, and the politics of course. I mean, academia always has been about petty politics, but now it’s all about the petty politics around revenues and costs. You don’t see most of it, thank your lucky stars. And me.”

“Uma sounds like a complete—”

“Yes. I’m not actually sure how much longer I’ll last if things keep going this way.”

“You’re planning to leave?”

“Or be replaced. Unless Uma goes.”

Ahmed frowned. “I had no idea things were this bad.”

“They’re worse than that. So I wouldn’t hold my breath for Ali’s departure if I were you, Uma has too much invested in this. Unless … ”

She trailed off, eyes narrowing.

“Unless?” Ahmed prompted.

“Unless Ali face-plants so badly … well, it doesn’t have a face, but you know what I mean.”

Ahmed began to agree, and then all of a sudden it hit him.

“Context and conflict!”

“What?”

“I think I might know how to assist Ali with that face-plant.”

“How?”

Ahmed smiled, for what felt like the first time in a long while.

“I have an idea.”

“Today’s class is going to be short, we have just the one concept to discuss.” Ahmed stood facing his camera, giving silent thanks to whoever had suggested placing his computer on a tripod; the ability to move around as he lectured had truly been liberating. At the bottom left corner of the screen, he could see Niyati, who’d shown up to observe the class herself this time. Excellent timing.

“We’re going to talk about the engine of plot development—conflict. Plots are driven by conflict, and the best ones are driven by conflict that’s high-stakes and has deeper ethical ramifications. So here’s what we’re going to do. I’m going to give you a conflict situation. A very specific one, with deep ethical considerations. It’s called the Trolley Problem. Ah, I see some of you know it. It’s a famous thought experiment. Picture a runaway trolley barreling down the railway track. Ahead, on the same track, there are five people tied up and unable to move. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However, you notice that there is one person on the side track. If you switch the tracks, the trolley will hit that person. What do you do? No, don’t answer me here, I want you all to mull over the problem. And then you’re all going to turn in an assignment that analyzes this conflict, its stakes, and ideal (or least unsatisfactory) resolution. Yes, this will count toward your final grade. Any questions? Yes, Peter?”

“Can we work on this with others?”

“Feel free to discuss it among yourselves or with other teachers, human or otherwise, indeed, I’d encourage you to do so, but remember that in the end, this is an individual assignment, so I want each of you to separately propose your own resolution. Anything else? No? Good. That’ll be all.”

He turned off his camera, feeling a tingling thrill of excitement course through him. He’d planted the seed. Now all he had to do was wait for it to sprout.

For the first time since he’d found out about it, he was looking forward to that midterm review.

“Hi Niyati!”

Ahmed beamed at her. He was in a good mood today. He’d heard that several students had actually broached the subject of the trolley problem with Ali, and that the results of such consultations had been “surprising,” although he didn’t actually know the details. Still, knowing what he did know about how the machine dealt with this sort of thing, it could only bode well for him.

“Morning, Ahmed. Shall we begin?”

Niyati was all business today, she didn’t even return his smile.

“Sure.”

“The observers have commended your handling of the class, your pedagogic manner, and your student interactions. The actual performance of your students has been good too. And for the most part, the student assessments have been positive. One student, Debanjana, I think her name is, has even mentioned how you listened to her issues.”

“Oh, that’s nice of her.”

“Very. Now let’s get to the not-so-positive stuff. I’ll be honest, Ahmed, I’d expected you to put some separation in feedback and results between you and Ali by this point. That hasn’t happened. For one thing, there was the complaint.”

“What complaint?” He wasn’t sure what he’d been expecting, but it hadn’t been this.

“A student called Mayil. He asked you for a special accommodation, which you denied, apparently.”

“Yes, I remember, that was because of—”

“I’m sure you had your reasons, but the fact of the matter is Ali granted the accommodation and you didn’t, and Mayil has written long statements to us about Ali’s superior empathy. Apparently Ali helped alleviate this student’s anxiety, and was instrumental in him not dropping out of the course.”

The room was still now, very still, He could hear his breath whistling out of his body. Almost dropped out? Because he, Ahmed, had simply said he shouldn’t stick with his own kind in class, and hadn’t cared enough to ask what the underlying issue had been?

“And then there’s the bit about your Trolley Problem assignment.”

“Yes, what about it?” Ahmed felt his chest tightening. This really wasn’t going anything like he’d anticipated.

“Apparently a few of your students mentioned it to Ali, who tore it apart.”

“Tore it apart? It’s a thought experiment, what the hell does that even mean?”

“From what I hear, Ali made a rather convincing case against the very premise of the exercise, and gave students an alternative conflict situation to parse instead.”

“Alternative? To the best-known ethical dilemma out there? How? What?”

“I don’t know the details, but the bottom line, Ahmed, is that this isn’t where we need you to be. Look, like I said, Uma has a lot riding on this Ali experiment. Unless it goes down, Uma doesn’t go down. And if Uma doesn’t go down, I do. And probably so do all the other teachers?”

“Uma wants to run a university without teachers?”

“Yes.”

“Is this a joke?”

“Not at all. Uma wants to take the concept of student assessment further, into student self- assessment. A university of the students, for the students and by the students. Want to know why we have Ali? That’s why.”

“The compromise!”

“Exactly.”

“This Uma is a runaway train looking for people to crush.”

“And right now we’re the ones tied to the tracks. I’m going to need you to find a way to separate from Ali, and quickly. Or we’re all done.”

He started to answer but she’d already disconnected. Ahmed swore, slamming his laptop shut. He’d have flung it against the wall, but it was the only one he had and if he didn’t separate, as Niyati had put it, he wouldn’t be able to afford another for a long time.

Ahmed spent most of the rest of the day staring into space, alone with his thoughts. He found his self-pity at the desperation of his situation giving way over time to a growing sense of guilt over a student almost dropping out because he’d refused to look deeper into his situation than a machine had cared to look.

Finally, he couldn’t take it anymore He took a deep breath, shook his head to clear the cobwebs, and flipped his laptop back open.

And then he sent a meeting request to Ali.

Within minutes, Ahmed’s computer pinged, Ali had responded and was waiting for him. The machine was nothing if not prompt. Ahmed logged in, and soon found himself staring at the empty space in the window that was Ali.

“You gave Mayil the accommodation he wanted?”

That was the good thing about talking to a machine, it neither desired nor expected the usual small talk.

“I did. Research has shown that familiarity in communication is a major anxiety reliever, especially in academic settings. I wanted my student to have everything he needed to succeed.”

If Ahmed hadn’t felt it earlier, he sure did now: a sharp sensation in his gut, the stab of shame. The machine had indeed proved to be a better mentor to Mayil than he had.

“I see.”

“You do not approve?”

“No, no, you did the right thing. I was wrong.”

“Yes.”

It was the agreement that annoyed him, cutting through the cloak of shame, and so he reached for the only accusation he had.

“You derided my assignment to our students!”

“I pointed out that the hypothetical was fundamentally flawed.”

“Flawed?” Ahmed laughed, a short bitter sound.

“Correct.”

“There’s no way you can back up that assertion. None at all.”

“Is that your theory? It is an interesting one, although as flawed as the original hypothesis.”

“It is, and yes, with the consent of the students, I have done so. They appreciate having past classes accessible to review.”

“Excuse me?” Ahmed couldn’t believe the cheek of this machine. Could machines even be cheeky? Probably not, but this one was being something, all right, and even if he didn’t have a name for it, he knew he didn’t appreciate it.

“Would you like to observe the pedagogical process by which we arrived at the conclusion?”

“We? You’ve forced this notion of yours on the students too?”

“There is no room for forcing conclusions on students in a functional educational setting. The concept was discussed, the conclusion arrived at via deliberation. Would you like to observe?”

“How? Have you been recording your classes? Is that even legal?”

“I—” Ahmed gritted his teeth, then unclenched them just as rapidly. Maybe fate was finally smiling on him. What better way to find the flaw in both the reasoning and the teacher than by observing it insist on something he knew was incorrect? “All right, yes, sure. Why not?”

“As you wish.”

A series of squares appeared on the screen, each one framing a face. Ahmed recognized every one, they were all students, his students. And Ali’s. Without realizing it, he found himself looking for the blank box that Ali always appeared as, and found he couldn’t spot it anywhere. A split second later it struck him why, he was looking at the class from Ali’s perspective. It was a somewhat unsettling realization, to know he was watching the world, or his class as the case was, through a machine’s eyes, not least because it looked exactly like it did through his own.

“All right, everyone,” Ali was saying. “Now that we’ve outlined the problem, from the original version Foot postulated, to the Thomson and Greene variants, can anyone outline the fundamentals of its construct? Yes, Debanjana?”

“It forces us to choose between actively and passively taking a life?”

“That is correct, it does. Is there anything else?”

Debanjana hesitated. “Is it that the problem itself is so removed from reality?”

“That it often fails the suspension of disbelief test required to address it adequately? Absolutely, correct again. But is there something more fundamental?” If nothing else, the earlier communication issues didn’t seem to exist any longer; Ali and Debanjana certainly seemed to be having no issues.

Debanjana hesitated. “I’m not sure.”

“Anyone else?”

There was silence in the class.

“The fundamental flaw here is that the problem, while posed as a dilemma, in fact has a simple solution.”

A buzz ran around the class. A series of questions rang out, all of them variations of “How?” and “What?” Ahmed smiled. The machine had stepped in it, and it didn’t even have feet.

“But as a thought experiment, isn’t there meant to be no solution?” asked someone finally.

“Bingo!” said Ahmed approvingly.

“Yes, isn’t it just about the reasoning?” asked another, a young man called Wang.

“Reason? Is it reasonable to tie five people to a railway track for an experiment?”

Watching, Ahmed felt his jaw tighten.

“But—”

“Why are there no safety measures to prevent someone from wandering onto the other track? Why is the very construction of the problem framed as a choice between innocent victims? Why does the safety of those in the trolley never enter into the discussion? And finally, why does the trolley not have an emergency brake?”

“But, but—” Now it was Ahmed stammering, although he wasn’t even in the class. Nothing he’d ever heard had prepared him for this. He tried to remember other words but they wouldn’t obey. “But—”

“The solution is simple: Stop the trolley!” Ali was talking to the students, but for all the world it felt like the machine was addressing him, Ahmed; it was as if everyone else had vanished. “To design a better one, one that stops. And do not choose between murder and murder. And certainly do not call a Hobson’s choice of this nature an ethical dilemma. There is nothing ethical about this scenario.”

Ahmed could see students nodding, murmuring in agreement, many of them looking as stunned as he felt.

The video shimmered and vanished, he was alone with Ali again, and feeling no less nonplussed for it. “I—” He opened his mouth, shut it again, and then repeated the process. There was no getting away from it, the machine was right. Again. If an ethics problem didn’t provide an opportunity for good, how ethical was it?

“Stop the trolley,” he repeated.

Long after the call, the sentence kept echoing through his head. Stop the trolley.

And there was more, Ali had now provided two separate solutions to two extremely different issues in a manner he, Ahmed, had failed to see, because he’d been thinking about what he wanted to say, what he thought, whereas the machine had prioritized the students and the issues themselves instead. It was a galling realization.

His phone rang, startling him, so he dropped it. Cursing, he retrieved it, and answered. It was Niyati. And she sounded happier than he’d heard her be since the year began.

“You did it!”

“Did what?”

“Exactly what we’d hoped! You’ve won. The trolley problem won!”

“Yes, about that, Niyati—”

“Don’t you see? You baited Ali into providing an alternate, and it did. Do you know what it came up with?” Her voice was quivering, he could virtually feel her excitement crackling through the phone.

“What?”

“Asked students to assess whether it is egalitarian for a university to provide services that depend on a student’s ability to access technology. Guess you were right, machines don’t do consequences well.” She laughed. “The Old Man is livid. Ali’s as good as gone. And Uma’s going to be gone with it.”

“The trolley.”

“What?”

“Uma’s the trolley.”

“You’re not making sense. Listen to me now, there’s a board meeting tomorrow morning. They’ll all be there, every last one of them. And so will we. You, me, Ali, the Old Man, the lot of us. I have a one-on-one with him tonight, and it’s done, I’m going to make sure Uma’s gone before morning. And then tomorrow morning we’ll watch him pull the plug on Ali in front of us all. Well done, Ahmed!”

“Look, Niyati, about that. I’m not interested.”

“In tenure?”

“In these competitions and frankly, in pushing out Ali, who is providing a genuine value addition to the department.”

“You want this machine to keep teaching? Do you hear yourself?”

“I do, but I’m done thinking about myself first. All I can do is the best I can do, which means doing the best for my students. Which means sticking up for Ali. For the rest, whatever happens, happens. Whether as a teacher or in support, Ali is doing well by students. And they’re doing well with Ali. I’ve seen it for myself.”

“Ahmed, you’re not going to ruin this for me, are you? Don’t you dare, I’ve put too much into this. You’d better be at that meeting tomorrow morning.”

“I’ll be there. But I’m not going to help shunt Ali out.”

Niyati’s nostrils flared. “I’m going to give you till morning to get your head on straight. Good night, Ahmed.”

And with that, she disconnected, leaving Ahmed sitting there with the knowledge that he’d just put everything he’d spent years working for on the line for his rival, a machine no less.

And he was fine with that.

Ahmed awoke the next morning feeling exactly as he had last night, and texted Niyati to let her know. Then he showered and dressed. With only a minute to go for the meeting, she still hadn’t replied. Ahmed shrugged, sat down, and clicked on the link to the board meeting, to be greeted by rows of windows. Almost immediately he spotted Ali, or rather his empty void. Then, as soon the Old Man entered, he began with the proceedings. Ahmed looked around for Niyati, but he didn’t see her. He frowned, puzzled.

Then he heard his name; the Old Man was talking to him. About him. Both.

“ … Ahmed here, who’s been so instrumental in this endeavor. I now hand over to the architect of our next phase.

“Thank you for doing this on such short notice, Ahmed.”

The window that was speaking was the one he’d first thought was Ali. But it wasn’t.

Ahmed stared open-mouthed, the cold realization hitting him in the chest like a bolt of lightning as he now focused on the name, emblazoned across the bottom of the empty window.

University Management Application.

Uma.

“I regret to inform you that Niyati is no longer with the University,” said Uma. “There’s been a change in plans.”

Read a response essay by Katina Michael, an expert on the social implications of technology.

More From Future Tense Fiction:

“The Truth Is All There Is,” by Emily Parker

“It Came From Cruden Farm,” by Max Barry

“Paciente Cero,” by Juan Villoro

“Scar Tissue,” by Tobias S. Buckell

“The Last of the Goggled Barskys,” by Joey Siara

“Legal Salvage,” by Holli Mintzer

“How to Pay Reparations: a Documentary,” by Tochi Onyebuchi

“The State Machine,” by Yudhanjaya Wijeratne

“Dream Soft, Dream Big,” by Hal Y. Zhang

“The Vastation,” by Paul Theroux

“Speaker,” by Simon Brown

“The Void,” by Leigh Alexander

And read 14 more Future Tense Fiction tales in our anthology, Future Tense Fiction: Stories of Tomorrow.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

"Short" - Google News

March 27, 2021 at 08:00PM

https://ift.tt/3tY0l8P

“The Trolley Solution,” a new short story by Shiv Ramdas. - Slate Magazine - Slate Magazine

"Short" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2QJPxcA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "“The Trolley Solution,” a new short story by Shiv Ramdas. - Slate Magazine - Slate Magazine"

Post a Comment