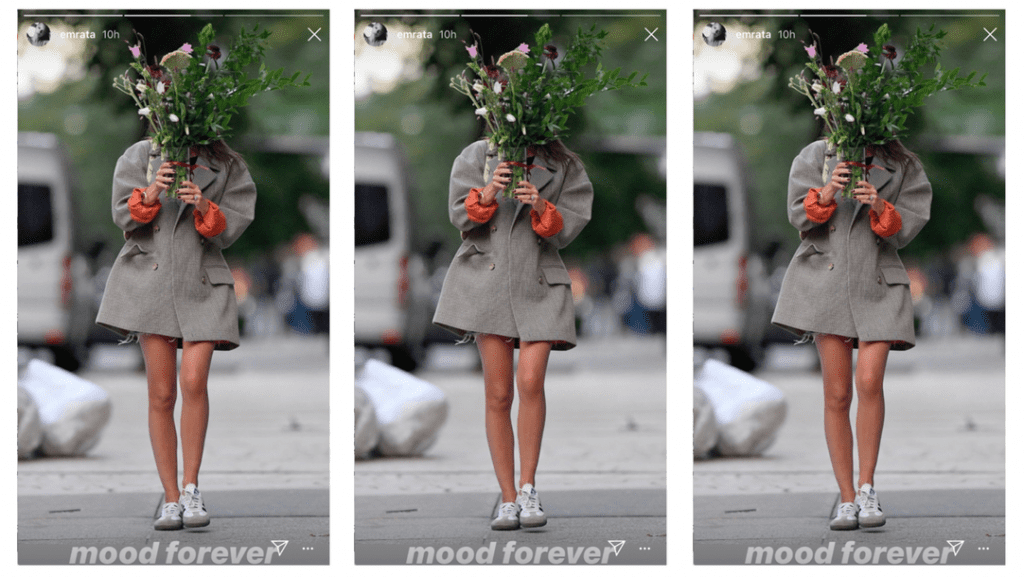

In October 2019, Emily Ratajkowski was sued for copyright infringement after posting a photo of herself to her Instagram account, captioning the photo in which she is obscuring her face with a flower arrangement with “mood forever.” The model-slash-actress would later argue in response to the copyright infringement lawsuit filed against her and her corporate entity by Robert O’Neil, the paparazzi photographer who took the photo, that her use of the image was fair use, as it served as a commentary on the state of her paparazzi-plagued life.

The basis of the lawsuit against Ratajkowski, which is still underway in a New York federal court, is hardly novel. In fact, since 2017 or so, which is when Khloe Kardashian was sued by Xposure Photos after sharing a photo of herself entering David Grutman’s restaurant Komodo in Miami on her heavily-followed Instagram without licensing it from the celebrity photo agency, a long list of nearly identical copyright cases have been filed against celebrities (and some fashion brands, as well) primarily in federal courts in New York and California for their unauthorized use of photos of themselves, the copyrights to which belong to third parties, namely, paparazzi photographers and/or the agencies that their assign their rights to.

Few celebrities have actively fought back in the increasingly lengthy list of paparazzi cases, and instead, have opted to settle suit out of court by paying undisclosed sums to the paparazzi photographer and/or photo agency defendants instead of choosing the more expensive and time-consuming alternative of defending themselves against such claims. A case filed against Gigi Hadid has proven to be an exception, with the supermodel making fair use claims and arguing that she was a joint author of the image at issue in the “meritless” case, and ultimately, prevailing in light of the defendant’s lack of a copyright registration, which is a prerequisite to filing a copyright infringement claim.

In addition to characterizing the suit as little more than a potential pay day for the paparazzi photo agency, Hadid’s counsel asserted that “it is an unfortunate reality of Ms. Hadid’s day-to-day life that paparazzi make a living by exploiting her image and selling it for profit,” emphasizing the ongoing argument about the dynamic of protection when it comes to photos under copyright law, namely, that protection can exist in a photo that was taken without a subject’s authorization, and that protection is granted to the “author” of a photo without considering the subject when it comes to awarding rights.

More recently, Ratajkowski has opted to challenge the copyright infringement lawsuit waged against her, and filed a motion for summary judgment last fall, arguing that the court should side with her in lieu of a full trial. The court sided with Ratajkowski, in part, and plaintiff Robert O’Neil, in part, meaning that the case will largely move forward to trial to determine a number of questions of fact.

As TFL reported recently, a lawsuit filed against singer Dua Lipa and a separate, newer suit filed against Ratajkowski, both of which in a California federal court in July, kick off the once-again-growing string of clashes between paparazzi and celebrities. The filings of these cases experienced a bit of a lull in 2020 in line with a more generalized drop in the initiation of new lawsuits were generally filed amid the pandemic.

“Mood Forever”

Not interested in simply settling the lawsuit filed against her for using his photo with authorization, Ratajkowski has taken to challenging O’Neil’s case, submitting in a motion in September 2020 in which she moved for summary judgment on the grounds that: “(1) the photograph is not the subject of a valid copyright, (2) Ratajkowski’s reposting was fair use, (3) O’Neil has not suffered damages, and (4) O’Neil’s cannot show facts establishing Ratajkowski’s involvement.”

In deciding on the motion in a order dated September 28, Judge Analisa Torres of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York quickly agreed to let Ratajkowski’s corporate entity Emrata Holdings off the hook, agreeing that O’Neil has not demonstrated Emrata Holdings’ liability. While “it is undisputed that Ratajkowski posts on the Instagram account in her personal capacity,” the judge stated that O’Neil “has demonstrated no facts linking Emrata to the copying of the photograph.”

Also dealt with in a relatively straightforward manner: Ratajkowski’s claim that the photo at issue is not the subject of a valid copyright, because it is “insufficiently original,” a finding that would take the infringement claim off the table. Siding with O’Neil, Judge Torres held that courts have previously “found paparazzi photographs original based on their ‘myriad creative choices, including, for example, their lighting, angle, and focus,’” and that not devoid of creative decision making, O’Neil “selected his location, lighting, equipment, and settings [for the photo] based on the location and timing.” Just because other photographers took photographs of “the same subject matter at the same time does not make the photo less original,” the judge stated, denying Ratajkowski’s motion on this front.

At the same time, the court shot down Ratajkowski’s claim that O’Neil did not establish that he is entitled to statutory damages (he is no longer seeking actual damages) due to the fact that the photo was only posted as a “sample” thumbnail on Splash’s website, which is accessible only to Splash subscribers, and thus, “was not published within the meaning of s. 412.” (No statutory damages are awarded for unpublished works, where the infringement commenced before the effective date of the registration, per s. 412 of the Copyright Act.) Unpersuaded, the court held that publication to Splash’s site meets the publication standard of s. 412, noting that “although Splash’s viewership is limited to its subscribers, that membership is a far cry from the ‘few trusted customers’ deemed too small a viewership for publication.”

The court also stated that O’Neil was “in a position to immediately realize the benefits of the photograph, and in fact, earned income on the photograph between September 13 and 19, 2021.” As such, the court found that he is not barred from recovering statutory damages for the infringement, and denied Ratajkowski’s motion for summary judgment based on lack of damages.

Fair Use

With those elements out of the way, Judge Torres spent the bulk of the order dissecting the merits of Ratajkowski’s claim that her posting of the photo amounts to fair use, and thus, she should be shielded from infringement liability. The court looked to the four non-exhaustive fair use factors, of course – (1) the purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work – in furtherance of its ultimate determination that it, well, could not decide, and thus, both parties motions for summary judgment on the issue of fair use should be denied.

From the outset, the court was largely unwilling to decide on the various fair use factors. On the purpose/character of the work, which comes with a number of sub-factors (transformativeness, commerciality, and bad faith), the court stated that reasonable jurors could disagree about whether or to what extent Ratajkowski’s use of the photo is transformative, noting a reasonable observer could conclude that Ratajkowski’s Instagram post “merely showcases Ratajkowski’s clothes, location, and pose at that time – the same purpose, effectively, as the photograph.” On the other hand, the judge held that “it is possible a reasonable observer could also conclude that, given the flowers covering Ratajkowski’s face and body and the text ‘mood forever,’ the Instagram [post] instead conveyed that Ratajkowski’s ‘mood forever’ was her attempt to hide from the encroaching eyes of the paparazzi – a commentary on the photograph.” As such, there is a genuine issue of material fact that needs to be decided by a jury.

As for the other sub-factors, the court found that Ratajkowski’s use was “slightly commercial,” but that this factor deserves “little weight” given the specific facts here. Among some of the noteworthy elements: the court held that Ratajkowski’s Instagram is, “at least in part, a for-profit enterprise,” as she “has a link to her for-profit store on the Instagram account main feed,” and she estimates that “she has made more than $100,000 from the Instagram stories section of the Instagram account within the last three years, although posting sponsored posts to Instagram Stories is less common than to her main feed.” The balance also tipped the other way to some extent in the commerciality assessment due to the fact that Ratajkowski was not paid to post the photo at issue, “nor was the infringed work displayed directly next to advertisements, or in a section almost exclusively meant for advertisements.”

The court was not convinced by O’Neil’s claim that Ratajkowski’s use was in bad faith because of “her ‘omission of any credit,’ and her [failure to pay] a license fee despite knowing that celebrities occasionally license photographs from Splash.” Judge Torres stated that while “Ratajkowski rarely credits photographers, there is no evidence that she personally removed copyright attribution from the photograph.” Beyond that, the court stated that “there is no evidence that Ratajowski knew the photograph was copyrighted or who it was copyrighted by,” and held that her mention of “general ‘internet etiquette’ that ‘people will share [her] images and [she] share[s] their images,’ does not demonstrate specific knowledge about the photograph or Instagram stories.”

Again, the judge held that “there is a genuine issue of material fact as to whether Ratajkowski’s use was transformative, and neither commerciality nor bad faith weigh heavily on the analysis— particularly if the use is deemed transformative.”

In terms of the second factor, the nature of the copyrighted work, the court determined that this weighs in favor of O’Neil, “but only marginally so” because the photo is “essentially factual in nature” and O’Neil “captured [his] subject in public, as [she] naturally appeared, and [was] not tasked with directing the subject, altering the backdrops, or otherwise doing much to impose creative force on the [photograph] or infuse the [photograph] with [his] own artistic vision.”

The court looked to the amount and substantiality of use of the photo next, and determined that Ratajkowski took “the vast majority, if not the entirety, of the photograph,” but also – interestingly – considered Ratajkowski’s argument that “by posting the photograph [via the temporary] Instagram Stories, rather than the main account, the use was less substantial.” The court sided with O’Neil on this factor, stating that “because Ratajkowski used a greater portion of the photograph than was necessary for her purpose, this factor weighs slightly in favor of the plaintiff.” However, “the fact that it was posted on Instagram Stories lessens that weight.”

Finally, on the effect on the market front, which requires a plaintiff to show that “even if the photograph is deemed transformative, a market exists which would be affected if this manner of using the photograph became widespread,” the court did not make a determination for either party, as “there is no information in the record regarding that market” for the court to “rule on this factor at this juncture.”

With the foregoing in mind, the court granted both parties’ motions in part and denied them in part, letting Emrata Holdings off the hook (and granting its motion for attorney’s fees and costs), denied a handful of the defendants’ affirmative defenses, and ultimately, left critical issue of fair use up to a jury.

One Final Question

A question to ponder here: Ratajkowski has not made a right of publicity counterclaim in response to O’Neil suit. Why? It might be because her face is obscured in the photo. It is worth noting that something of a similar issue came up in another recent SDNY decision. In a September 22 order in the Champion v. Moda Operandi case, Judge Colleen McMahon stated that the use of images that show runway models’ bodies – but in which their faces were either “cropped out, shown from the back, or indiscernible because they are part of a crowd of models” make it so that the models “cannot recognized by a viewer of Moda Operandi’s website” – cannot give rise to false endorsement claims under the Lanham Act. In photos in which their faces do not appear, the models “are effectively anonymous,” which is important, as “the misappropriation of a completely anonymous face [cannot] form the basis for a false endorsement claim, because consumers would not infer that an unknown model was ‘endorsing’ a product.”

Moreover, Judge McMahon held that “the very fact that their faces are not identifiable renders the allegation that Moda Operandi intended to trade on the good will associated with their personas totally implausible,” and as a result, dismissed some of the models’ Lanham Act claims against Moda.

The case is O’Neil v. Ratajkowski et al, 1:19-cv-09769 (SDNY).

"celeb" - Google News

October 01, 2021 at 08:52PM

https://ift.tt/3kX2BLU

Celeb v. Paparazzi Battle Over Emily Ratajkowski's "Mood Forever" Instagram Post Must Go to a Jury - The Fashion Law

"celeb" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2SoB2MP

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Celeb v. Paparazzi Battle Over Emily Ratajkowski's "Mood Forever" Instagram Post Must Go to a Jury - The Fashion Law"

Post a Comment